by Ian Maule

William Poteet has a gift to be able to do college level math at the age of ten. While many people see this as lucky, William must walk a delicate balance between achieving his academic potential and fitting in socially with his peers.

by Ian Maule

William Poteet has a gift to be able to do college level math at the age of ten. While many people see this as lucky, William must walk a delicate balance between achieving his academic potential and fitting in socially with his peers.

Each Thursday, WKU’s Student Chapter of NPPA brings you some of the best images of the past week taken by our very own classmates. To submit for our weekly posts, you must currently be a WKU Photojournalism student and have taken the images or produced the video within the last week (Tuesday to Tuesday). Send your top 1-5 selections to wkunppa@gmail.com by our Tuesday 6:30pm deadline and our officers and attendees will pick the best of the bunch to showcase at our open meetings every Tuesday at 7pm in Lab 127.

Lace Bellamy, of Owensboro, Ky., sits in anticipation on her wedding day as her bridesmaids help put on her pink converse shoes. BRITTANY GREESON

Lace Bellamy, of Owensboro, Ky., sits in anticipation on her wedding day as her bridesmaids help put on her pink converse shoes. BRITTANY GREESON

Alayna Milby, May 7, 2014. Shot through diffraction grating material. ADAM WOLFFBRANDT

Alayna Milby, May 7, 2014. Shot through diffraction grating material. ADAM WOLFFBRANDT

A contender for Saturday’s Kentucky Derby, Hoppertunity, was scratched, while some of his rivals got early baths on Thursday. JABIN BOTSFORD

A contender for Saturday’s Kentucky Derby, Hoppertunity, was scratched, while some of his rivals got early baths on Thursday. JABIN BOTSFORD

Victor Espinoza finishes 1 3/4 length ahead of the field atop California Chrome to win the 140th Kentucky Derby on May 3, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Victor Espinoza finishes 1 3/4 length ahead of the field atop California Chrome to win the 140th Kentucky Derby on May 3, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

A scene of patrons in attendance for Kentucky Oaks at Churchhill Downs, May 2, 2014. ADAM WOLFFBRANDT

A scene of patrons in attendance for Kentucky Oaks at Churchhill Downs, May 2, 2014. ADAM WOLFFBRANDT

Spectators occupy a bench in the paddock of Churchill Downs between races on Oaks Day, May 2, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Spectators occupy a bench in the paddock of Churchill Downs between races on Oaks Day, May 2, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Horses are washed in the barn area during morning training and preparation on the day of the 140th Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Ky., on Saturday May 03, 2014. JABIN BOTSFORD

Horses are washed in the barn area during morning training and preparation on the day of the 140th Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs in Louisville, Ky., on Saturday May 03, 2014. JABIN BOTSFORD

Maria Grantes grazes Diamond on the backside of Churchill Downs Derby Day on May 3, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Maria Grantes grazes Diamond on the backside of Churchill Downs Derby Day on May 3, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Each Thursday, WKU’s Student Chapter of NPPA brings you some of the best images of the past week taken by our very own classmates. To submit for our weekly posts, you must currently be a WKU Photojournalism student and have taken the images or produced the video within the last week (Tuesday to Tuesday). Send your top 1-5 selections to wkunppa@gmail.com by our Tuesday 6:30pm deadline and our officers and attendees will pick the best of the bunch to showcase at our open meetings every Tuesday at 7pm in Lab 127.

During a calm amidst thunderstorms, Rebekah “Birdy” Jessup explores a flooded area in her back yard on Monday, April 28, 2014. Photo taken with iPhone 5, filtered with Cross Process app. DANNY GUY

During a calm amidst thunderstorms, Rebekah “Birdy” Jessup explores a flooded area in her back yard on Monday, April 28, 2014. Photo taken with iPhone 5, filtered with Cross Process app. DANNY GUY

Lauren Tucker, 18, rests on the wheelchair of Karlie Hempel, 16, while the girls wait to cross the street in Owensboro, Ky., on March 28, 2014. Lauren volunteers at Puzzle Pieces, a daycare and activity center for community members with special needs, where she met Karlie. “I tell her everything, and she’s not gonna tell anyone,” says Lauren, “and what she tells me I’m not gonna tell anyone. We just kind of have a connection that I’ve never had with anyone else before.” SHELLEY OWENS

Lauren Tucker, 18, rests on the wheelchair of Karlie Hempel, 16, while the girls wait to cross the street in Owensboro, Ky., on March 28, 2014. Lauren volunteers at Puzzle Pieces, a daycare and activity center for community members with special needs, where she met Karlie. “I tell her everything, and she’s not gonna tell anyone,” says Lauren, “and what she tells me I’m not gonna tell anyone. We just kind of have a connection that I’ve never had with anyone else before.” SHELLEY OWENS

Joey Penn blows smoke bubbles during Mayhem Music Festival at Circus Square Park on Friday, April 25, 2014. The festival is an annual event hosted by WKU’s college radio station, Revolution 91.7. TYLER ESSARY

Joey Penn blows smoke bubbles during Mayhem Music Festival at Circus Square Park on Friday, April 25, 2014. The festival is an annual event hosted by WKU’s college radio station, Revolution 91.7. TYLER ESSARY

Adbdel Ramirez rests after attending mass on Friday, April 25, 2014. Ramirez is a Cuban refugee who has chronic spine problems and is experiencing the first signs of Alzheimer’s. Because he does not speak English, he has trouble communicating his problems and needs at the doctor’s office. He believes God is the reason he made it safely to America. “God is my life, God is my everything. God is the reason I still exist today.” JUSTIN GILLILAND

Adbdel Ramirez rests after attending mass on Friday, April 25, 2014. Ramirez is a Cuban refugee who has chronic spine problems and is experiencing the first signs of Alzheimer’s. Because he does not speak English, he has trouble communicating his problems and needs at the doctor’s office. He believes God is the reason he made it safely to America. “God is my life, God is my everything. God is the reason I still exist today.” JUSTIN GILLILAND

Big Mike Mic Whoa grew up in the inner city of Chattanooga. He said growing up he went through many struggles like poverty and gang violence. After His friend was shot and almost killed, Big Mike Mic Whoa took it upon himself to stop the violence. TYLER ESSARY

Each Thursday, WKU’s Student Chapter of NPPA brings you some of the best images of the past week taken by our very own classmates. To submit for our weekly posts, you must currently be a WKU Photojournalism student and have taken the images or produced the video within the last week (Tuesday to Tuesday). Send your top 1-5 selections to wkunppa@gmail.com by our Tuesday 6:30pm deadline and our officers and attendees will pick the best of the bunch to showcase at our open meetings every Tuesday at 7pm in Lab 127.

Members of St. Joseph’s Church carry out a procession for the Host in the Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament to the Altar of Repose, on April 17, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Members of St. Joseph’s Church carry out a procession for the Host in the Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament to the Altar of Repose, on April 17, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

A Catholic church member prays to the Altar of Repose on Holy Thursday of Lent at St. Joseph’s Church on April 17, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

A Catholic church member prays to the Altar of Repose on Holy Thursday of Lent at St. Joseph’s Church on April 17, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Freshman Ciara Sherrod of Whitehouse, Tenn., is an active dancer at WKU. She has performed in several shows on campus including the “Dance Project,” in which dancers learned a routine in a week for the show. Shot through a fish tank. ADAM WOLFFBRANDT

Freshman Ciara Sherrod of Whitehouse, Tenn., is an active dancer at WKU. She has performed in several shows on campus including the “Dance Project,” in which dancers learned a routine in a week for the show. Shot through a fish tank. ADAM WOLFFBRANDT

Freshman Vanessa Price practices for her upcoming performance at The Evening of Dance on Saturday April 19, 2014 in Bowling Green, Ky. JEFF BROWN

Freshman Vanessa Price practices for her upcoming performance at The Evening of Dance on Saturday April 19, 2014 in Bowling Green, Ky. JEFF BROWN

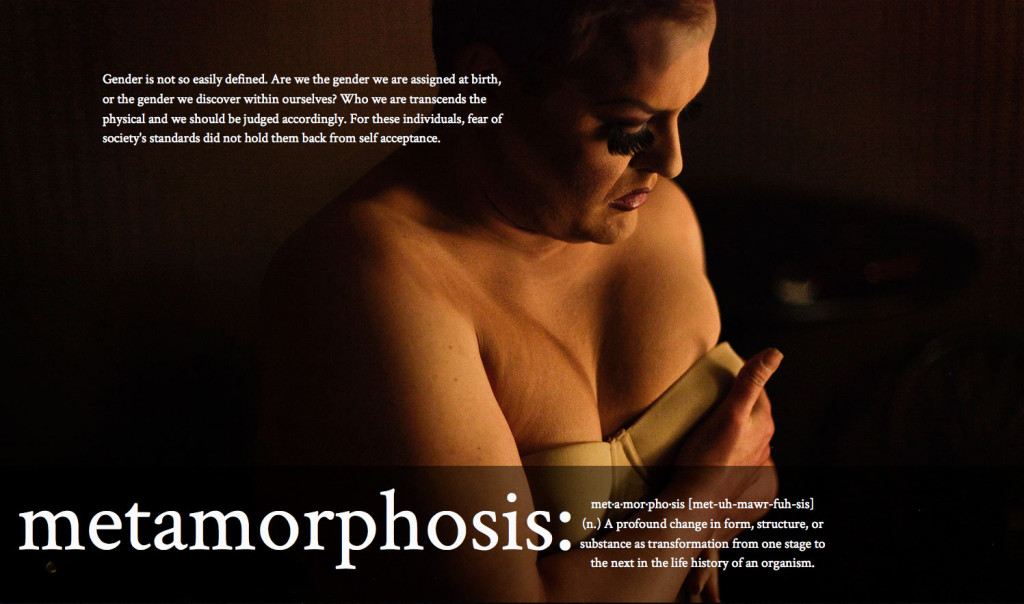

This week, we highlight Metamorphosis, a group multimedia project created by WKU students, as part of our ongoing series entitled Focus On, which showcases some of the extraordinary talent coming out of the photojournalism program at Western Kentucky University.

As the group’s mission statement reads, “gender is a complex topic that, in some ways, many are unfamiliar with. There are no black and white answers for sexuality and gender identification. This project is a collection of work documenting people that are not afraid to share their true selves with the world.”

As the group’s mission statement reads, “gender is a complex topic that, in some ways, many are unfamiliar with. There are no black and white answers for sexuality and gender identification. This project is a collection of work documenting people that are not afraid to share their true selves with the world.”

To visit the website and view their stories, click here. Continue reading below for an interview with a few members of the team as they recount their experience working on the project.

—

NPPA: How did this all start, and how did the team come together?

Adam Wolffbrandt (Producer): One of our professors approached me about the idea to organize a group project centered around gender issues. After doing a project on a transgender man, I had strong connections with stories surrounding gender identity. Within about a week, we were able to gather content from other students with similar stories and built a team of designers, developers and writers to put it all together.

I’ve worked with groups before, but with this project the team was so much more connected. We all depended on each other for the role they played. My coding knowledge and writing skills were limited, so counting on those people we recruited was crucial. Sometimes a group dynamic can be rough, but the whole process went so smooth. We had the same goal in mind and put it together more seamlessly than I could’ve imagined.

NPPA: How were you able to write the code for the website?

Rae Emary (Design & Development): The website for Metamorphosis is an all-encompassing collection of the skills Brandon and I learned in our separate Interactive Media classes, literally. We utilized many of the codes we had completed, and used them as a basis for the site. Without the codes we had previously wrote, the project would have been much more time-consuming. Personally, completing the coding class has allowed me the freedom as a creative spirit to create and be a part of things I can be proud of. Before the class, I wasn’t sure about design, and had little to no grasp on how to properly present media. Now, however, I feel confident in my ability as a visual journalist to not only create stories but present them on a clean, visually appealing platform.

NPPA: How do you think editing all of the content that was being considered helped shape the project?

Justin Gilliland (Editing): We had an awesome collage of photos but there wasn’t uniformity. I think those quotes we added brought them together to be an essay and to have a greater impact. Before, they were beautiful photographs, and putting all the content together, the words, photos, videos, everything, it became what it was supposed to be, a team project, but more importantly, a statement. Focusing all this great content and helping it come together to speak common ground within itself and to its viewers brought it to the next level and that’s what I was brought on to do. The quotes I got and connection I made with our characters work with the photos that captivate the audience. Those quotes and those photos turn viewers into readers, and vice-versa, so when you look at it you can’t help but feel an impact. That takes content and makes it into real emotion and that’s what it’s all about.

NPPA: What were some of the problems you all faced along the way?

Brandon Carter (Design & Development): Rae and I each brought different things to the table, which helped a lot in the wee hours of the morning in the lab. Two of our biggest problems – the navigation bar and how to handle the photo essay – were both fixed after hours of pounding away at their respective codes. We spent a long time tweaking those things to make them work absolutely perfectly, and also making them work on multiple devices.

The biggest antidote to our late nights in the lab was Adam and Justin being right there with us, banging out edits on the photos, videos, captions, and story. They were timely, and always seemed to have stuff finished before Rae and I could even fathom putting it into the working code. The all-nighters were awesome, both for the sake of productivity and for bonding. By the end of it, we became a well-oiled machine, and I think that’s one of the reasons the project turned out so beautifully.

Congratulations to the three finalists who ranked highest in our WKU NPPA Greek Week Shootout! The winners were chosen by a majority-rule ballot vote by those in attendance at this week’s Through Our Eyes meeting and were awarded signed prints from members of our own faculty!

1rst. IAN MAULE

Louisville senior Abigail O’Bryan sings “You’re the One That I Want,” from the movie Grease with fellow members of Alpha Gamma Delta while waiting to perform their routine at Spring Sing at Diddle Arena on Sunday, April 6, 2014

Louisville senior Abigail O’Bryan sings “You’re the One That I Want,” from the movie Grease with fellow members of Alpha Gamma Delta while waiting to perform their routine at Spring Sing at Diddle Arena on Sunday, April 6, 2014

2nd. JABIN BOTSFORD

Members of Kappa Delta-Delta Gamma, “The Green Army,” pull for their 10th consecutive win of Tug on Friday, April 11, 2014, at L.D. Brown Ag. Expo. Center. Tug is an annual tug-of-war competition for Greek Week, pitting organizations against each other for the championship title.

Members of Kappa Delta-Delta Gamma, “The Green Army,” pull for their 10th consecutive win of Tug on Friday, April 11, 2014, at L.D. Brown Ag. Expo. Center. Tug is an annual tug-of-war competition for Greek Week, pitting organizations against each other for the championship title.

3rd. BRITTANY GREESON

Nashville sophomore Jazmyn Bethel weeps as she waits for her sorority, Sigma Kappa, to compete in the semi-finals of the annual Greek Week tug competition. “We worked all semester.” said Bethel. “It’s different from Spring Sing. I put my whole heart in and you want it so bad, yet you have three minutes to prove yourself.”

Nashville sophomore Jazmyn Bethel weeps as she waits for her sorority, Sigma Kappa, to compete in the semi-finals of the annual Greek Week tug competition. “We worked all semester.” said Bethel. “It’s different from Spring Sing. I put my whole heart in and you want it so bad, yet you have three minutes to prove yourself.”

Each Thursday, WKU’s Student Chapter of NPPA brings you some of the best images of the past week taken by our very own classmates. To submit for our weekly posts, you must currently be a WKU Photojournalism student and have taken the images or produced the video within the last week (Tuesday to Tuesday). Send your top 1-5 selections to wkunppa@gmail.com by our Tuesday 6:30pm deadline and our officers and attendees will pick the best of the bunch to showcase at our open meetings every Tuesday at 7pm in Lab 127.

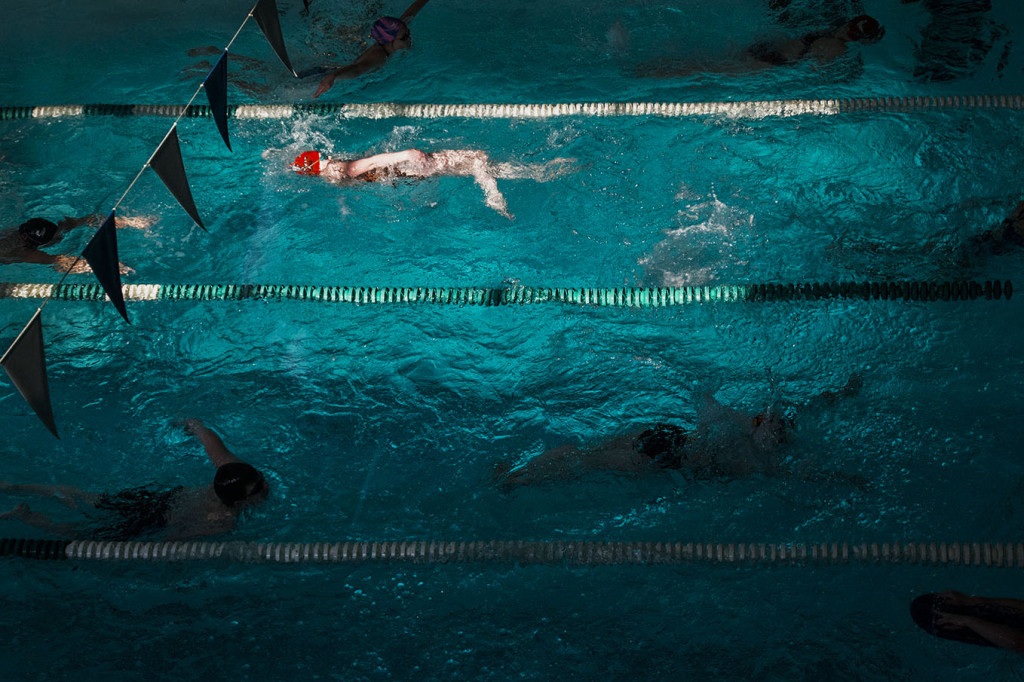

The junior group of the Falcons Club Swim Team practices on Wednesday, April 16, 2014, at the YMCA of Greater Flint. KATIE MCLEAN

The junior group of the Falcons Club Swim Team practices on Wednesday, April 16, 2014, at the YMCA of Greater Flint. KATIE MCLEAN

WKU fraternity members compete in the 40-yard-dash during the Greek Week Events Day at the Colonnade on WKU’s campus on Thursday, April 10, 2014. Events included the 40-yard-dash, Ball Race, Sack Race, Egg Spoon Race, Egg Toss, Musical Chairs, and the Penny Toss. BRIAN POWERS

WKU fraternity members compete in the 40-yard-dash during the Greek Week Events Day at the Colonnade on WKU’s campus on Thursday, April 10, 2014. Events included the 40-yard-dash, Ball Race, Sack Race, Egg Spoon Race, Egg Toss, Musical Chairs, and the Penny Toss. BRIAN POWERS

Franklin Senior Mary Clayton Kinslow of AOPI celebrates with her sorority after their performance for the annual Greek Week Spring Sing Competition. Kinslow is the only senior in her sorority. BRITTANY GREESON

Franklin Senior Mary Clayton Kinslow of AOPI celebrates with her sorority after their performance for the annual Greek Week Spring Sing Competition. Kinslow is the only senior in her sorority. BRITTANY GREESON

Kappa Delta sorority member Grace Cockrum embraces Kennedy Harden after winning the annual Greek Week Tug Competition at the Western Kentucky University Agriculture Farm in Bowling Green, Ky. Kappa Delta has won the competition 11 years in a row. HARRISON HILL

Kappa Delta sorority member Grace Cockrum embraces Kennedy Harden after winning the annual Greek Week Tug Competition at the Western Kentucky University Agriculture Farm in Bowling Green, Ky. Kappa Delta has won the competition 11 years in a row. HARRISON HILL

Alpha Delta Pi practices cheers for Spring Sing outside of their house on April 5, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Alpha Delta Pi practices cheers for Spring Sing outside of their house on April 5, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

This week, we present WKU senior Demetrius Freeman’s photo essay he created while studying abroad at the Danish School of Media and Journalism last spring as part of our ongoing series entitled Focus On, which highlights some of the extraordinary talent coming out of the photojournalism program at Western Kentucky University.

Train Ride to the End of the World: Hoyerswerda

During the time of the GDR, Hoyerswerda was a powerful, fast-growing industrial town in the Saxony state of eastern Germany. Glass factories, coal mining, and power plants provided thousands of jobs forcing the demand for housing to dramatically rise in a short period of time. Hoyerswerda was a model city of the east increasing the population from 24,549 in 1960, to 34,095 in 1963, to 53,472 in 1968. The peak was reached in 1981 when the population hit 72,000 people. Thousands of apartment complexes were built in order to meet the demand.

In 1990, with the end of the GDR and the reunification of Germany, the economy was reorganized causing thousands of jobs to disappear. Power plants reduced staff, factories closed, and buildings emptied as people moved west for better opportunities.

With the loss of these jobs, Hoyerswerda began shrinking at a rapid rate, as more and more people moved to bigger cities like Berlin and Dresden for better opportunities. The population average age rose as the students and young people left the city. Hoyerswerda was left with empty factories, businesses, streets, and thousands of empty apartments. The fear is not only of Hoyerswerda shrinking, but fear for the future existence of the city itself.

An old restaurant on the outskirts of town that has been transformed into a home. All the surrounding apartments have been demolished.

An old restaurant on the outskirts of town that has been transformed into a home. All the surrounding apartments have been demolished.

An old painting of Mickey Mouse inside of what used to be a family home. When the factory shut down the residences moved leaving the neighborhood abandoned.

An old painting of Mickey Mouse inside of what used to be a family home. When the factory shut down the residences moved leaving the neighborhood abandoned.

Paint peeling from the wall of an empty apartment complex. The apartment was filled with families and workers from the glass factory but when it closed everyone moved to other places leaving the small community empty.

Paint peeling from the wall of an empty apartment complex. The apartment was filled with families and workers from the glass factory but when it closed everyone moved to other places leaving the small community empty.

The last building structure that stands on the outskirts of town. This building has on tenant and is scheduled to be demolished.

The last building structure that stands on the outskirts of town. This building has on tenant and is scheduled to be demolished.

An empty desk inside of the old glass factory outside of Hoyerswerda.

An empty desk inside of the old glass factory outside of Hoyerswerda.

Broken glass from an abandoned home across the street from the closed down glass factory. When the factory closed the neighborhood emptied as everyone migrated to Dresden and Berlin for better job opportunities.

Broken glass from an abandoned home across the street from the closed down glass factory. When the factory closed the neighborhood emptied as everyone migrated to Dresden and Berlin for better job opportunities.

A paper cutout sits in the window of a home in a next to Hoyerswerda. The village is scheduled to be demolished so that the mining company, Vattenfall, can begin mining coal where the village stands.The company has built a duplicate town 6 miles from the original town.

A paper cutout sits in the window of a home in a next to Hoyerswerda. The village is scheduled to be demolished so that the mining company, Vattenfall, can begin mining coal where the village stands.The company has built a duplicate town 6 miles from the original town.

————

NPPA: What lead you to this story?

DF: Some years ago I read an article about Detroit, and it’s issues with job loss and a fast-shrinking population. Reading the article made me ask, is this issue happening in other places, if so why, and more importantly, could the survival of a city be based solely on the economic diversity of the city? Is this the beginning of a new society issue that will hurt smaller cities, towns, etc.? Will we all migrate to bigger cities? All of these thoughts crossed my mind and I began researching where this was happening in the world other than Detriot. If Detroit the extreme case, was it economic based? More questions meant more research. Then I came across a New York Times Article from 2009 about Hoyerswerda, Germany. The article explained the issue of shrinking populations, the aging community, and the lost of jobs, but visually I had no idea what these places were like. So I decided that once I returned to Europe I was going to do a photo story there.

NPPA: What story are you trying to tell with these images?

DF: The goal of these images is to provide a photographic landscape of Hoyerswerda and the feeling of isolation, destruction, and emptiness.

NPPA: What has been the most rewarding part of the story for you?

DF: Personally, working on this story has really made me open my eyes to other cultures, languages, and has made me more aware that there are issues that need a voice everywhere. This project made me fear what could happen, embrace what did happen, and sympathize with people with a level of understanding that was gained through listening and asking. Having the opportunity to focus on a single project for a longer period of time was such a joy to me. At first I was nervous because I have never worked on something for a long period of time, but as the story went on I felt that I connected on a deeper level than just the surface. The most rewarding would have to be the relationships I established. I met some awesome people in Hoy who showed interest in who I was and allowed me to explore their world and tell me part of their story.

NPPA: What was the most challenging part?

DF: This project made me step out of my comfort zone, which is an extremely challenging thing to do. I traveled to a place I had never been before, where most people do not speak English, where Neo Nazis have a strong presence, and where seeing a dark-skinned person is a very rare sight. While in Hoyerswerda I was confronted by a Neo Nazi advocate who spoke strong words about “Hail Hitler and Only Whites should be on the earth.” This was the first time I had ever had a direct verbal racism attack, which made me feel out of place for a moment but because I did my research and found a fixer, she was able to defuse the situation. This encounter was a reminder that racism still remained and that I must continue forward and not let such things harm who I am.

NPPA: What has been the most important thing you have learned?

DF: The experience I gained from working on Train Ride to the End of the World: Hoyerswerda has been very rewarding for me both professionally and personally. Professionally I have become an overall better journalist. Though I took photographs, the most important and time-consuming moments were during researching, planning, and interviewing. I learned how to look at and analyze the research material to find my angle. I learned how to plan for a trip, scheduling my time with several subjects within a day, and I learned the importance of having a fixer. This has given me confidence in traveling to places where the culture and the language is different. I also learned how to communicate better during interviews, allowing the subject to speak freely gave more details and important information that also makes them feel a part of the project and thus gives it a better result.

Photographically, I have gained the confidences and trust in my skills, the ability to tell a story in a different form than linear, and a stronger ability to show meaning in a photograph that is normally done with text. I learned how to adjust my visual style to fit with the dominating material and how to collaborate and be more open minded about photo selection.

This project taught me more about myself and helped me learn and overcome new challenges while creating lasting memories and relationships. Experiences is what I live for so I encourage others to take that chance, buy that ticket and go explore. Thanks! -DF

Each Thursday, WKU’s Student Chapter of NPPA brings you some of the best images of the past week taken by our very own classmates. To submit for our weekly posts, you must currently be a WKU Photojournalism student and have taken the images or produced the video within the last week (Tuesday to Tuesday). Send your top 1-5 selections to wkunppa@gmail.com by our Tuesday 6:30pm deadline and our officers and attendees will pick the best of the bunch to showcase at our open meetings every Tuesday at 7pm in Lab 127.

Logan Beckham, 17, twirls a burning T-shirt during a riot after University of Kentucky was defeated by the University of Connecticut on April 07, 2014. Beckham recently got kicked out of high school for possession of marijuana. HARRISON HILL

Logan Beckham, 17, twirls a burning T-shirt during a riot after University of Kentucky was defeated by the University of Connecticut on April 07, 2014. Beckham recently got kicked out of high school for possession of marijuana. HARRISON HILL

Two men hang out of a limousine during the NCAA championship game on State St. while calling out at pedestrians to join them. The men yelled out at rioters passing by, claiming differing identities such as “porn stars from California” and the posse of Jennifer Lawrence. ALYSE YOUNG

Two men hang out of a limousine during the NCAA championship game on State St. while calling out at pedestrians to join them. The men yelled out at rioters passing by, claiming differing identities such as “porn stars from California” and the posse of Jennifer Lawrence. ALYSE YOUNG

University of Kentucky fans celebrate by climbing a tree on State St. The UK Wildcats defeated the Wisconsin Badgers 74-73 on April 5, 2014. MICHAEL NOBLE JR.

University of Kentucky fans celebrate by climbing a tree on State St. The UK Wildcats defeated the Wisconsin Badgers 74-73 on April 5, 2014. MICHAEL NOBLE JR.

UK students try to wake up an unconscious man after being knocked out by another rioter after University of Kentucky lost in the NCAA National Championship against University of Connecticut on April 07, 2014. HARRISON HILL

UK students try to wake up an unconscious man after being knocked out by another rioter after University of Kentucky lost in the NCAA National Championship against University of Connecticut on April 07, 2014. HARRISON HILL

A University of Kentucky fan screams in protest as Lexington police officers carry him to a police car away from rioting on State Street in Lexington, Ky following the University of Kentucky’s NCAA Championship loss against the University of Connecticut. The young man was detained after becoming aggressive with other crowd members. BRITTANY GREESON

A University of Kentucky fan screams in protest as Lexington police officers carry him to a police car away from rioting on State Street in Lexington, Ky following the University of Kentucky’s NCAA Championship loss against the University of Connecticut. The young man was detained after becoming aggressive with other crowd members. BRITTANY GREESON

A couple celebrates the UK victory over Wisconsin in the Final Four at 202 State St. on April 5, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

A couple celebrates the UK victory over Wisconsin in the Final Four at 202 State St. on April 5, 2014. JUSTIN GILLILAND

Alex Kandel, lead singer of Bowling Green band Sleeper Agent, performs at the Warehouse at Mt. Victor on April 5, 2014. The hometown group returned to their roots in Bowling Green after a long hiatus away on tour. They performed with Buffalo Rodeo, another Bowling Green group, and Knox Hamilton. (shot through a glass prism) LUKE FRANKE

Alex Kandel, lead singer of Bowling Green band Sleeper Agent, performs at the Warehouse at Mt. Victor on April 5, 2014. The hometown group returned to their roots in Bowling Green after a long hiatus away on tour. They performed with Buffalo Rodeo, another Bowling Green group, and Knox Hamilton. (shot through a glass prism) LUKE FRANKE

Chi Omega junior Hannah Bobinger of Hendersonville, Tn., practices singing alone in a hallway before going on stage to perform during Spring Sing at E.A. Diddle Arena at Western Kentucky University on Sunday, April 6, 2014. DOROTHY EDWARDS

Chi Omega junior Hannah Bobinger of Hendersonville, Tn., practices singing alone in a hallway before going on stage to perform during Spring Sing at E.A. Diddle Arena at Western Kentucky University on Sunday, April 6, 2014. DOROTHY EDWARDS

Each Thursday, WKU’s Student Chapter of NPPA brings you some of the best images of the past week taken by our very own classmates. To submit for our weekly posts, you must currently be a WKU Photojournalism student and have taken the images or produced the video within the last week (Tuesday to Tuesday). Send your top 1-5 selections to wkunppa@gmail.com by our Tuesday 6:30pm deadline and our officers and attendees will pick the best of the bunch to showcase at our open meetings every Tuesday at 7pm in Lab 127.

Katie Norman, 19, waits behind the baptistery with her uncle, Ed Norman, 56, on the morning of Sunday, March 30, 2014. Ed has been battling liver cancer for the past 17 months, which has significantly affected his energy, making it difficult to perform simple tasks like walking or talking. Katie asked her uncle to baptize her after hearing his testimony. “I wouldn’t miss this for the world,” said Ed. SHELLEY OWENS

Katie Norman, 19, waits behind the baptistery with her uncle, Ed Norman, 56, on the morning of Sunday, March 30, 2014. Ed has been battling liver cancer for the past 17 months, which has significantly affected his energy, making it difficult to perform simple tasks like walking or talking. Katie asked her uncle to baptize her after hearing his testimony. “I wouldn’t miss this for the world,” said Ed. SHELLEY OWENS

A man jumps over a burning couch on University Avenue as thousands of fans stormed State Street and University Avenue after University of Kentucky beat the University of Louisville in Lexington, Ky., on Friday, March 28, 2014. JABIN BOTSFORD

A man jumps over a burning couch on University Avenue as thousands of fans stormed State Street and University Avenue after University of Kentucky beat the University of Louisville in Lexington, Ky., on Friday, March 28, 2014. JABIN BOTSFORD

Thousands of fans stormed State Street after University of Kentucky beat University of Louisville in Lexington, Ky., on Friday, March 28, 2014. JABIN BOTSFORD

Thousands of fans stormed State Street after University of Kentucky beat University of Louisville in Lexington, Ky., on Friday, March 28, 2014. JABIN BOTSFORD

A student tries to wake up an unconscious fan after the University of Kentucky win over University of Louisville during the sweet sixteen NCAA tournament on March 28, 2014. Hundreds of students flooded the streets after the win to burn couches, break stop signs and climb light poles. HARRISON HILL

A student tries to wake up an unconscious fan after the University of Kentucky win over University of Louisville during the sweet sixteen NCAA tournament on March 28, 2014. Hundreds of students flooded the streets after the win to burn couches, break stop signs and climb light poles. HARRISON HILL

Sharon Graham gets some fresh air outside her home at Bowling Green Towers on Friday, March 28, 2014, in Bowling Green, Ky. Graham celebrated one year of not smoking two days prior. Graham smoked for 35 years until her granddaughter was born and realized smoking prevented her from seeing the child. “I made up my mind that I had to see her and have her in my life. That’s what got me going to quit smoking,” she said. CASSIDY JOHNSON

Sharon Graham gets some fresh air outside her home at Bowling Green Towers on Friday, March 28, 2014, in Bowling Green, Ky. Graham celebrated one year of not smoking two days prior. Graham smoked for 35 years until her granddaughter was born and realized smoking prevented her from seeing the child. “I made up my mind that I had to see her and have her in my life. That’s what got me going to quit smoking,” she said. CASSIDY JOHNSON

Kevin Cross stands in the hallway of his home at Bowling Green Towers on Friday, March 28, 2014, in Bowling Green, Ky. Cross has been all over the country working various jobs, including traveling with the circus, bouncing at a bar, and being a DJ. He finally came to Bowling Green to move closer to his girlfriend. “How you are doing depends on your view of the grass: you’re either looking down at the blades or up at the roots,” he said. CASSIDY JOHNSON

Kevin Cross stands in the hallway of his home at Bowling Green Towers on Friday, March 28, 2014, in Bowling Green, Ky. Cross has been all over the country working various jobs, including traveling with the circus, bouncing at a bar, and being a DJ. He finally came to Bowling Green to move closer to his girlfriend. “How you are doing depends on your view of the grass: you’re either looking down at the blades or up at the roots,” he said. CASSIDY JOHNSON

Megan Lemmons models MAC lipstick in Bowling Green, Ky. ALYSSA POINTER

Megan Lemmons models MAC lipstick in Bowling Green, Ky. ALYSSA POINTER

Brad Ausbrooks has been collecting tattoos since he turned 18. Now, he has been working for Carter’s Tattoo Company in Bowling Green, Ky., for 11 years. KREABLE YOUNG

Growing up a fiddle player, Frank Beauchamp combines his love for music with his passion for teaching. The fifth grade school teacher has been at Caverna Elementary School in Cave City, Ky., for nine years and has brought his fiddle with him every day. He plays before during and after school and says it can provide a welcome break for both him and the students during the day. BRIAN POWERS