“It made me question if I was holding the right tool, but a camera is the tool of my trade,” – Michael Bunch

Twenty years ago WKU Photojournalism students decided to journey to NYC and Washington DC to document the biggest historical event in their lives, the September 11 attack. Recently WKU President Gary Ransdell looked back on that day and remembered hearing that students from the Photojournalism program had decided to drive to NYC to cover the tragedy. He explained his first reaction was concern for their safety but quickly understood we are training them to be journalist and that is what journalist do.

MARK ANDERSON

Under different circumstances, a weeklong trip to New York City for three college students would have been a lot of fun. But 852 miles away, history was happening.

Within a couple of hours of hearing of the devastation on September 11, 2001, I was in a car along with two other photojournalism students from Western Kentucky University.

In Bowling Green, Kentucky, I’d left behind a week’s worth of classes, four very understanding professors and two very frightened parents on the other end of a telephone.

“Be careful,” my dad said.

How fortunate that my mom had not answered the phone. I don’t think I could’ve told her where I was going.

On the road, we listened to radio reports of what was happening. We didn’t know what we would find when we got there, or if we’d even get there.

We were scared.

We arrived in New York in the early morning hours of September 12. Lights from the worksite at Ground Zero illuminated the smoke still drifting over the city.

I spent four days in New York, photographing the pain, the devastation, but mostly the indomitable human spirit that was alive everywhere around the magnificent city.

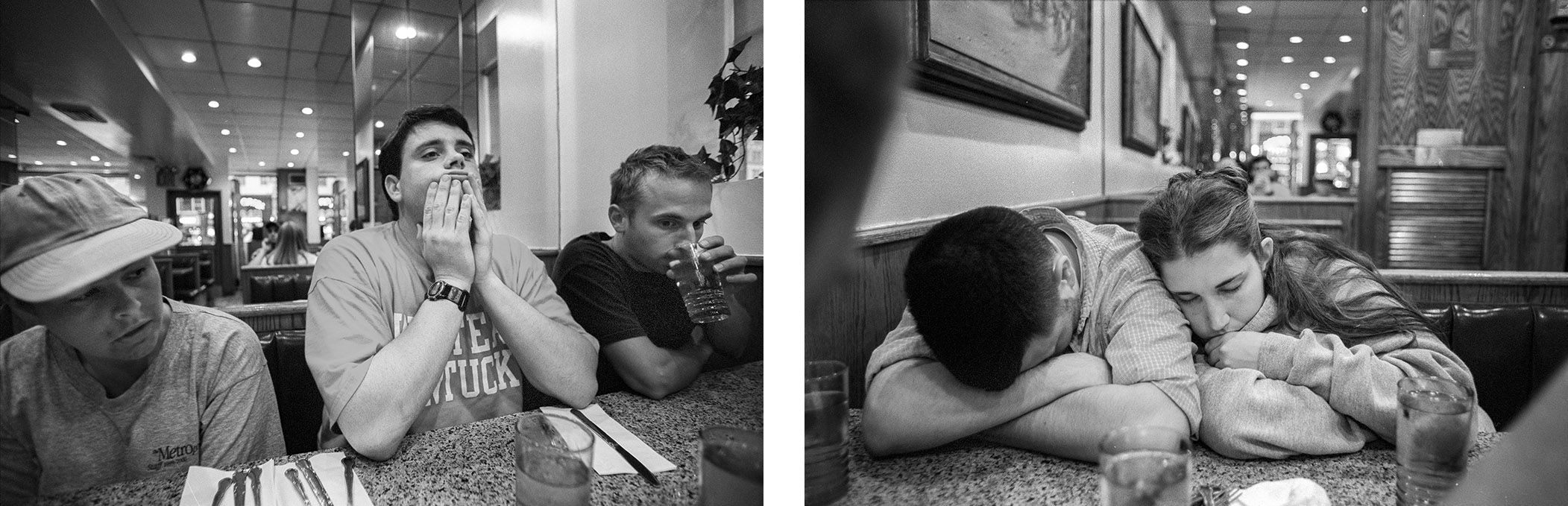

The feeling there was much different than we had expected. People were shocked and dazed, but friendly and polite — nothing like the rude New Yorkers you hear about or see in the movies. They had wanted to talk about what happened to them and the country and what was still happening.

During our third night, after walking around for a couple of hours, trying hard not to be noticed, it began to rain. We eventually found shelter beneath an awning only a couple of blocks from ground zero. The three of us huddled together because it was very cold.

I remember just how miserable I was and then began thinking of the people who were still trapped inside the remains of the smoldering towers and how cold and wet and alone they must have felt. That was the moment that it really felt personal.

Going to New York to photograph the attacks isn’t something I’m proud of; it’s just something I did. I didn’t have to think about going. I had the opportunity to see something that I knew would forever change our country, and I went.

JAMES BRANAMAN

There was a lot of self-doubt covering such a large-scale event as a student, especially not knowing exactly how, if ever, the images would be used.

There was discussion before we even left about whether it was responsible to go and possibly add further strain to a chaotic situation, but a few other students and myself felt very strongly a need to document this tragic moment in history.

So, when one of us secured a place to stay in the city we drove all night and arrived on the morning of September 12.

I went into the situation thinking I was covering an event that had already happened, but the truth was that the story was still unfolding, with repercussions that would be felt for many years to come.

The gravity of the situation washed over me after seeing hundreds of faces on “missing” posters plastered across the city as many people had not yet officially been declared deceased.

Our first night we photographed people gathered at makeshift memorials in parks near Ground Zero, with some of us finally putting away our cameras to help each other deal with the overwhelming feeling of sorrow and tragedy.

The next day, when F-16 fighter jets screamed overhead at low altitude, the thought crossed my mind, will they attack again?

YULI WU

The morning of September 11, I woke up to an ABC Special Report as Peter Jennings reported that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center North Tower.

In class with journalism professor Mrs. Albers, we watched the World Trade Center South Tower get demolished by a highjacked plane. I remembered the class was silent as everyone was in disbelief.

Two of my classmates and I made the decision an hour later to drive 12 hours to New York City to document the event.

As we stood close to Ground Zero, we witnessed chaos and bravery from the people of New York. We documented the event as best as we could. I remembered the drive home was depressing. Throughout the night, I was terrified, and what-ifs kept repeating in my mind.

What if they target a small town such as Bowling Green or my hometown of Ann Arbor, Michigan? What’s going to happen next? The unknowns were uneased.

I remember September 11 as if it was yesterday. My mental wellness was affected, and thousands of Americans suffered.

What we witnessed on TV and in person was a nightmare that became a reality that day.

May the heroes of New York City be remembered.

ANDREAS FUHRMANN

I was working on a photo story when I saw live news coverage of the 9/11 attack. Going up to New York was the talk among us. Some went right away. Others like myself waited a few days, and then decided to go.

For me, my hesitation came from not wanting to get in the way. I wasn’t a working journalist with an outlet (so I thought) so I didn’t feel I had a reason to be there. I changed my mind after a couple of days and four of us drove up. I decided that it was too big of an event to not go.

I was a nontraditional student in my early thirties. Another person I went up with was also older. The others were young college kids, and all of us handled ourselves wonderfully in such a raw situation.

The New Yorkers were extremely receptive and welcoming as well. I can’t recall anyone turning away from a camera. Everyone was on the same page when it came to documenting this horrific event.

Over the years, and more recently, I have found my thoughts drifting to the image I made on that trip of a woman looking at the Jasper Johns American flag painting in the Museum of Modern Art days after the attack. I wonder what she was thinking then, and now. I wonder what many of us are thinking about our country.

As for New York right after the attack, one typically doesn’t get to experience humanity on this level in a lifetime.

It is hard to believe that, until the other day, we’ve been at war ever since that day 20 years ago. In that time, I’ve again changed careers. I’ve seen my classmates go on to have families, their children never knowing us not at war.

Going up to New York and covering the tragedy of 9/11 was something we needed to do. I believe we are better for it.

NINA GREIPEL

I was young, and while very independent, I hadn’t been to a big city on my own since I was a kid with my parents.

I am glad Jenny Sevcik and MJ Mahon decided to tag along in my car. Along the drive we heard from others that they had either turned around, or decided to drive to Washington, D.C., instead. We kept heading towards New York and finally arrived late in the evening on 9/11 and checked into a hotel in New Jersey.

When we entered New York City on September 12, we made our way into Tribeca, where we could see a parade of vehicles delivering water and supplies to the nearby rescue crews.

We kept walking south. The sun was shining and there was a lot of noise from people hollering at the rescue vehicles, and just in general there was a lot of commotion. As we turned into a quieter side street, I saw a firefighter sitting on a stoop, his uniform dirty and his hands over his face, crying. I just remember that so vividly because I was wondering what we were about to experience.

When I was there with my family as a kid, I do remember one thing very vividly: it was a big and impersonal city. People would pass each other by, not speaking to each other, ignoring each other, keeping to themselves.

On September 12, 2001, it was a completely different feeling. Small groups had formed on the streets and in the parks. Strangers were randomly interacting with each other sharing stories and information. It felt more like a small village rather than a big city.

This was even more noticeable in areas where people had posted “missing” posters with pictures of their loved ones. Seeing those is what really made it real for me. So many posters and so many loved ones missing. It was gut wrenching.

I am glad I had the opportunity to experience one of the biggest news events in history with my camera and my classmates, though I wish I never would have had the reason to go.

I was 27 and not yet that experienced in photojournalism, but it was a valuable lesson. It was not only a lesson in how to approach people who were in anguish but also how to deal with my own anguish and emotions after returning from it all.

MICHAEL BUNCH

Twenty years after 9/11, l remember the human spirit much more than I remember the destruction and chaos.

I recall watching vehicles roll in from all over the country, sedans strapped with wheelbarrows and shovels, covered in makeshift signs stating they’d traveled to New York City to help in any way possible.

It made me question if I was holding the right tool, but a camera is the tool of my trade, so I focused on finding images that showed less the tears and rubble and more how remarkable people can be in the wake of immense tragedy.

DAVID COOPER

I’m not sure what I expected as we drove toward New York on the Thursday after September 11, 2001. As we got closer, we could see across the Hudson River. I saw the smoke still rising from Ground Zero. The tragedy became real with such sadness.

Twenty years later, I certainly remember that sadness as we documented those few days. But I mostly remember the resiliency of New Yorkers. They pulled together for the common good. The country did the same. I hope for that feeling of unity now.

AMY SMOTHERMAN BURGESS

When I think back this is what I remember:

- Listening

- Shock at the size of the hole in the earth.

- Watching hope turn to despair and grief.

- Not being able to focus my camera through tears, but still shooting.

- Feeling the importance of documenting the events of September 11, 2001, knowing that the future would be changed.

JAMES KENNEY

As my colleague, David Cooper, and former student, Amy Smotherman Burgess, and I drove into New York City in the wee hours of the Friday morning after 9/11, with smoke still rising from where the twin towers once stood on the city skyline, I remember thinking to myself, “This is not how I wanted to see New York City for the first time.”

I grew up in Los Angeles, but my father, who died when I was 17, grew up in New York. Perhaps because of this the city had always held a special, almost mystical place in my mind and heart. I had always dreamed of traveling to New York City to walk the streets that my father walked as a child. But instead, I was walking these same streets photographing destruction, disbelief, pain, tears, and the faint hope that those missing were still alive.

By the end of the weekend, hope had faded. The reality of what happened had fully set in.

I came in sadness and left in sadness. I brought home photographs and audio, stories that I hoped would make some sense of it all, or at least make some difference. Beyond my prayers, this was all I had to offer.

JED CONKLIN

It’s my first time in New York City.

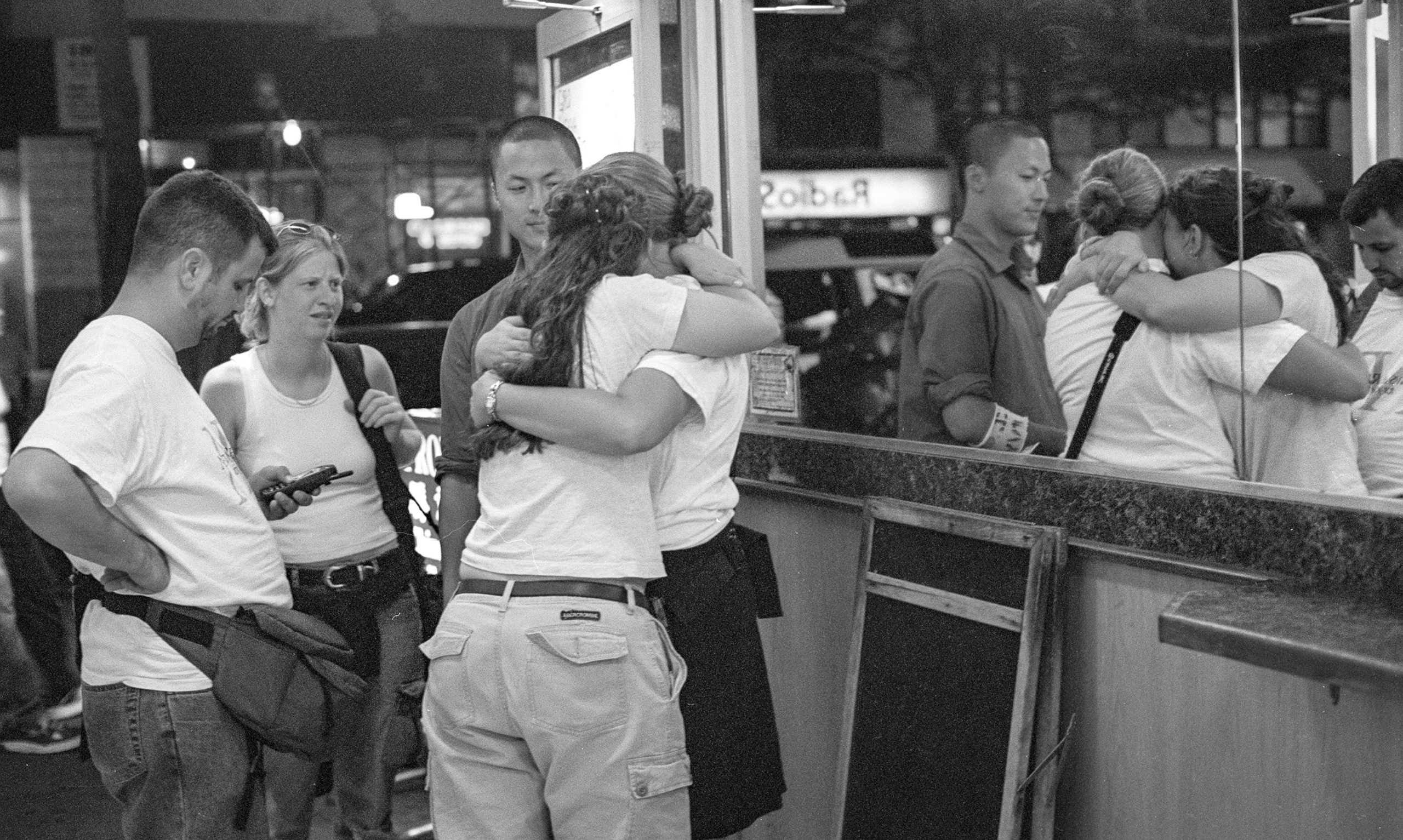

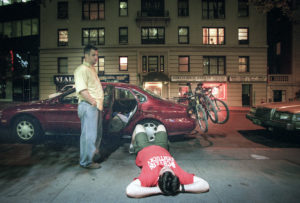

The buildings tower over the chaotic streets. An acrid haze diffuses the September sun and the endless lines of flashing emergency lights. Every road and sidewalk leading to Ground Zero is locked down. Every park has huddled masses. Many people are crying, wrapped by the consoling arms of strangers. Candles, teddy bears, flowers, and keepsakes are set up in impromptu memorials throughout the city. It appears every lamppost is hauntingly decorated with the faces of the missing – the phone numbers of their loved ones boldly printed, pleading for someone to call with good news.

It is quieter than I expected, as if we were all at a wake and being loud would be disrespectful. And so, it is with quiet and careful steps that we move about the city doing what we are trained to do.

We photograph what we see today so it is not forgotten tomorrow.

IMAGES CAPTURED BY OUR STUDENTS IN THE AFTERMATH OF 9-11