Srijita Chattopadhyay

During her internship, WKUPJ student Srijita Chattopadhyay followed a Rohingya refugee family as they observed 40-days of mourning after the accidental death of their son.

The original story can be seen in the San Antonio Express-News

https://www.expressnews.com/40-days-mourning-photo-essay/?cmpid=gsa-mysa-result

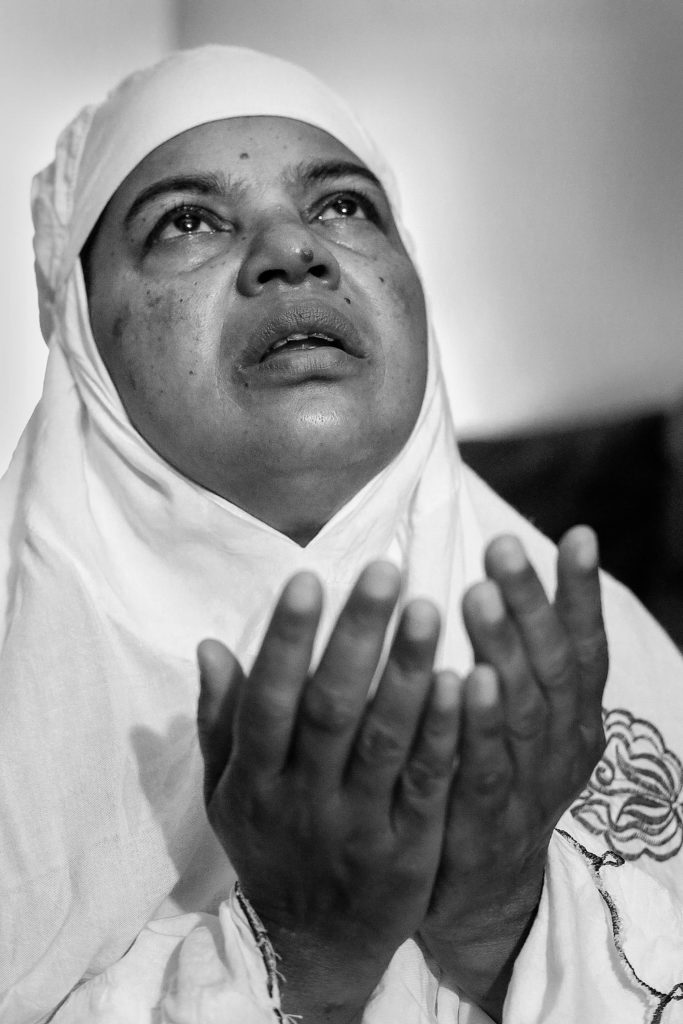

Sitting on the floor of her affordable housing in San Antonio, Zahidah Begum Binti Ali Miah raises her hands in prayer. To Allah she requests, “take care of my son,” and then slowly exhales, “help me find peace.”

August 12, 2017, marked the end of a 40-day mourning period for Mohamad Sharib’s family. Ordinarily, Islam calls for three days of mourning. But, for the family, a 40-day observance is a cultural variation in their Muslim faith.

On July 7, 2017, Zahidah requested to see her son one more time after the customary ritual of gusal (bathing and cleaning of the deceased) to say her last goodbye. “My son. My good son,” Zahidah kept chanting, as her younger son, Mohamad Emran, along with relatives, escorted her out of the morgue.

Laying her head on her husband’s lap, Zahidah takes a moment to look over at her grandson to make sure he is asleep. As days pass by and Mohamad Sharib becomes a memory, Zahidah feels his absence in the family. “Sharib would always take care of me,” she said with tears in her eyes. “He would cook food, make tea, give me medicines on time and massage my shoulders when I would feel pain. Now I have no one.”

Zahidah endures the pain of the loss by herself. She feels that her husband does not understand her. “He tells me to get over it and live for my other son and my grandchildren,” she said. “But how can I do that?”

Gabriel Scarlett

While interning for The Denver Post in the summer of 2017, WKUPJ student Gabriel Scarlett began traveling to Pueblo, Colorado, a rust belt town known for its gang culture. His ongoing essay focuses on the community’s resilience.

A full essay can be viewed on his website

http://www.gabrielscarlett.com/their-eyes-on-high#1

Julian Rodriguez plays with his son Christopher at their home on Pueblo’s East Side. Julian’s decades-long struggle with addiction brought him intimately close to the gang operations as he often bought from and sold for the gangs in order to support his own addiction. With his son, Christopher on the way, he reached sobriety and had his facial skeleton tattooed to remember his commitment to his son and to commemorate his brother “Bone Head” who was killed in a shootout with the police. “Everything that I desire and want in this life is for that boy.” Christopher will grow up on the East Side, in Duke territory, but Julian hopes that a loving relationship with his father can keep him from that lifestyle.

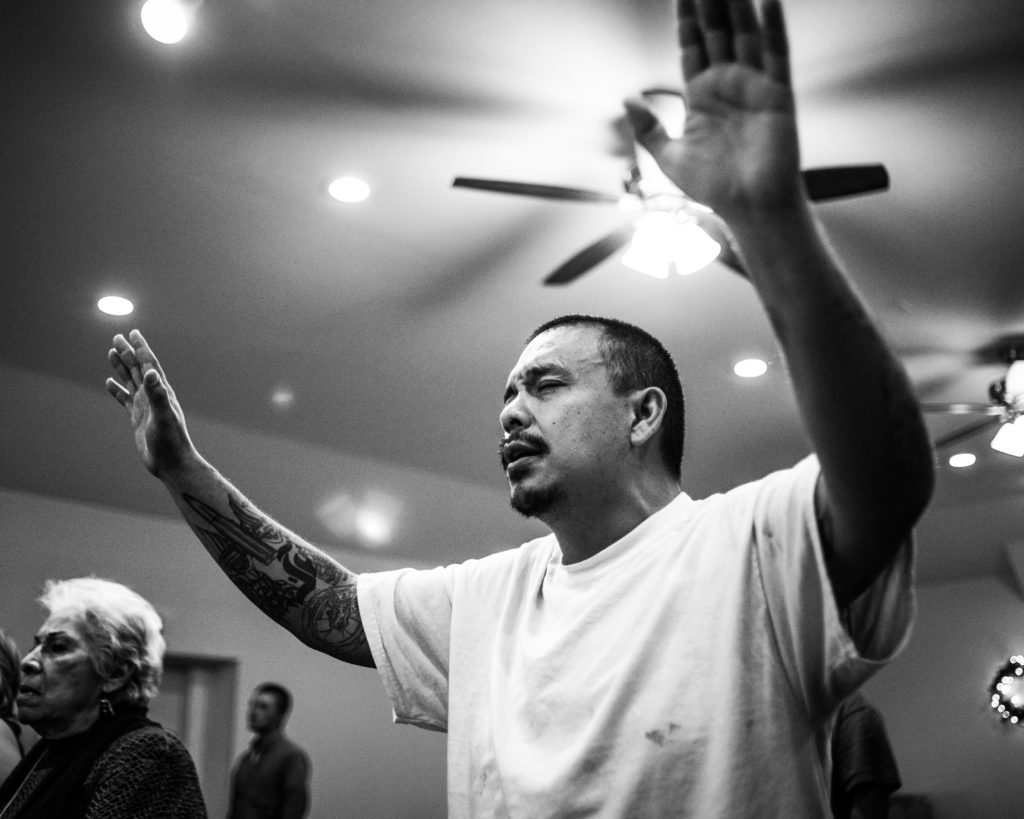

Felix Rubio praises at New Hope Ministries, a front lines church in Pueblo that openly accepts addicts, alcoholics, gang members, and anyone else seeking God. As a gang member in Denver, Felix recalls his life as a warrior, a “beast,” owning machine guns and moving kilos of product from his apartment. His drug use kept him up for days and even weeks at a time, until he checked himself into a faith-based rehabilitation program. When people look at him now, Felix wants them to see “Jesus, bro. Jesus. When I was in the hood, I wanted them to see me. When they see me now, I want them to see Jesus’ likeness.”