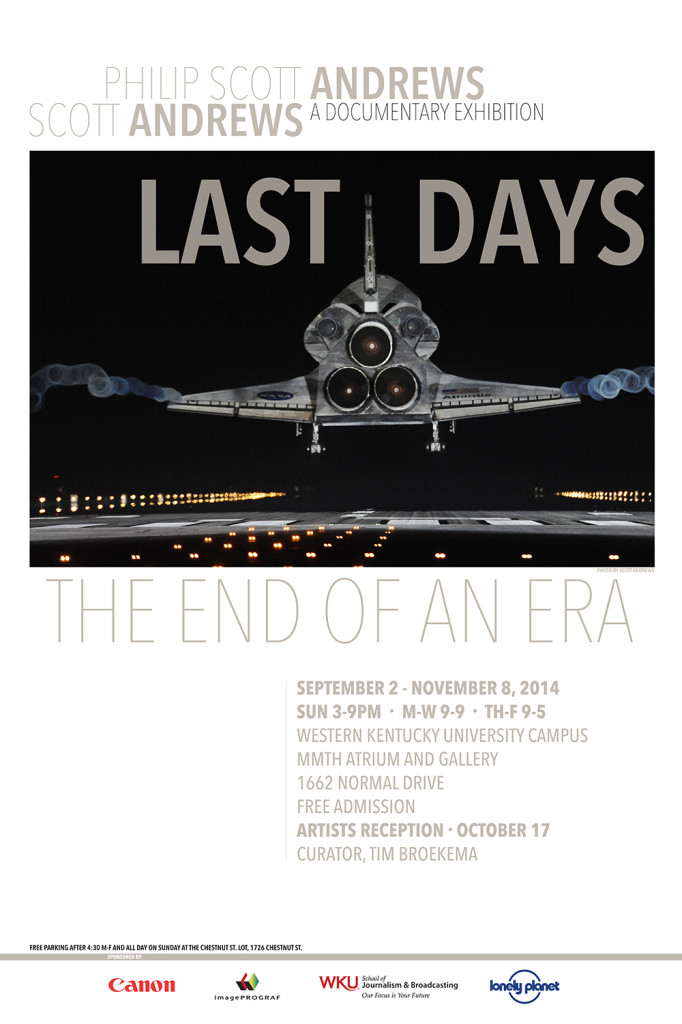

The School of Journalism and Broadcasting is excited to announce the opening of Last Days: The End of An Era, a documentary exhibition by Scott Andrews and his son Philip Scott Andrews (WKU, 10) that explores humans and their relationship with machine.

After 30 years of flight, NASA’s Space Shuttle Program was halted and the remaining four shuttles were retired to museums. The photographs and time-lapse video in this exhibition of more than 50 prints and two multi-media installations curated by WKU photojournalism professor Tim Broekema, tell a story about men and women who showed up to work everyday; and launched spaceships. It is a marvel, a symbol of the United States’ twentieth century dominance. But it is a tragic story, a farewell livelong to a bygone era.

It is intended that this work will serve as a partial archive; as a tribute to the men and women who spent their lives (some of whom, sadly, gave their lives) making spaceflight a daily activity. In looking back, we can look ahead to find the next adventure over the distant horizon.

Exhibition Dates

September 2 – November 8, 2014

October 17, reception and special guests (TBA)

Mass Media and Technology Hall Atrium and Gallery

Western Kentucky University campus

1660 Normal Dr.

Bowling Green, KY 42101

Free admission and open to the public*

Sunday 3:00 – 9:00 pm

M-W 9:00 am – 9:00 pm

TH-F 9:00 am – 5:00 pm

*Please note the gallery will be closed October 2-3 for fall break.

This Exhibition would not have been possible without the generosity from:

Canon, USA

Canon, ImagePROGRAF division

Lonely Planet

WKU School of Journalism and Broadcasting

Free parking is available after 4:30 M-F and all day Sunday at the Chestnut St. lot located at 1726 Chestnut St.

Scott Andrews

Gene Cernan and Tom Stafford did not give a thought to a 12-year-old photographer named Scott Andrews in the early morning hours of June 3, 1966. The two astronauts had just strapped themselves into the cockpit of their Gemini 9 spacecraft — a tiny pod into which they were crammed shoulder-to-shoulder, nose-to-instrument panel, atop 109 ft. of Titan missile. Two launch attempts had been scrubbed already, and for this third one, the back-up astronauts — Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin — had left a teasing little note in the cockpit: “We were kidding before, but not anymore, get your…uh…selves into space, or we’ll take your place.”

Cernan and Stafford did get into space that day, and when their Titan lit, at 6:38 AM ET, Andrews was there, watching his first-ever manned launch, snapping and snapping and snapping away. He came back for Gemini 10 as well, and then 11, and then 12, and nearly all of the Apollos, and Skylabs and shuttle missions that followed. By college, he was photographing the launches professionally. The only three manned liftoffs he missed in his long career were two of the 135 shuttle launches and that of the ill-fated Apollo 13.

If you’ve seen pictures of a shuttle launch, chances are you’ve seen the results of his handiwork. For more than 40 years, Scott Andrews has been photographing launches and landings, and he’s aided hundreds of photographers from around the world.

Philip Scott Andrews

By the time Philip Scott Andrews was born, the space shuttle program was six years old, in full swing and easy to take for granted. Yet Philip has always been fascinated with space travel. You could say he was born into it. His father, Scott Andrews, a photographer and then technical consultant to Canon, has been covering NASA since Project Gemini in the mid-1960s and has photographed 133 of the 135 shuttle missions.

“When the end of the program was announced, we knew we had a limited time to do something special,” Philip said. What they did — “Go to Launch,” an extended time-lapse video showing the mind-boggling scale of flight preparation — is indeed special. But their work scarcely stopped there.

Philip also used a camera loaded with black-and-white film to create “Last Days (in Progress),” an unusually intimate glimpse behind the scenes as the shuttle program geared up for the last mission. These pictures are classic examples of diligent documentary practice, combining persistence, patience and artistry.

To say nothing of ingenuity. given the great distance that separates photographers from the launching pad, the only way to get close is to use remote cameras. “A lot of people don’t realize the amount of work that goes into making an image of the shuttle lifting off the pad,” Philip said. “It takes about three to four days to get all the cameras together, hooked up to their triggering devices and deployed into the field.”

With all the uncertainty around America’s future space travel after the shuttle, Philip can be sure of one thing. “I grew up with it,” he said. “I think I will really start to feel a hole when it lands for the last time. My dad and I spent three years of our lives securing access and photographing scenes few people have ever witnessed. It has been quite a bit of work, but I have felt humbled and privileged every minute I have been at the space center.”

For further information or to schedule a school group tour please call 270-745-4144